Summary

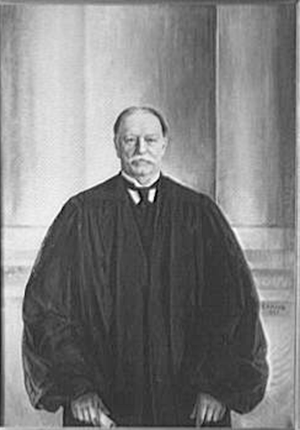

Olmstead v. United States was one of the most important early cases interpreting the Fourth Amendment. In Olmstead, federal agents suspected that Roy Olmstead was running an illegal liquor business during the height of Prohibition. Without a judicial warrant, the agents installed wiretaps on the phone lines leading to the office of Olmstead’s business, as well as to Olmstead’s home and to those of his suspected accomplices. The wiretaps were installed on the parts of the phone lines in the public street and in the basement of the office building. Able to listen to the suspect’s phone conversations, the agents uncovered evidence that Olmstead was selling liquor and arrested him. In a 5-to-4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the government’s use of wiretaps had not violated the Fourth Amendment. For the Court majority, a Fourth Amendment violation required an actual physical examination of one’s person, papers, physical effects, or home. On this view, the government’s use of wiretaps was not a search because it did not involve a trespass on Olmstead’s property and because the government had not seized any of his physical papers or effects. However, in a powerful dissent, Justice Louis Brandies disagreed. There, Brandeis challenged the Court to translate old constitutional principles to meet the challenges of new contexts and emerging technologies—arguing that the Court must read the Fourth Amendment in such a way that it protected at least as much privacy as in the Founding era. Decades later, the Supreme Court would embrace Brandeis’s insights in Katz v. United States (1967).