Summary

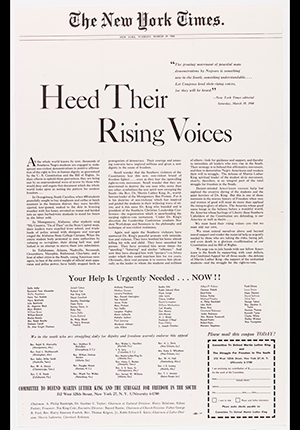

Sullivan was a defamation case decided in the throes of the Civil Rights Movement that was then surging throughout the United States. The New York Times published a full-page advertisement on behalf of African Americans and clergymen in Alabama who were then combatting the Jim Crow laws; the ad accused various Alabama officials of violence and other wrongdoing, but many specific statements were conceded afterward to have been false. The question, which endures to this day, is how much falsity does the First Amendment tolerate in the context of political speech and public officials?