Historic Document

Constitutional Government in the United States (1908)

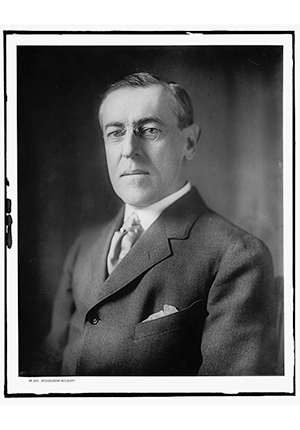

Woodrow Wilson | 1908

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Summary

A Virginia-born and Johns Hopkins-trained political scientist, Princeton University President, and New Jersey Governor, Woodrow Wilson was one of the country’s leading constitutional scholars before entering politics as a progressive reformer, and being elected President of the United States. Wilson’s extensive scholarship was focused on the relationship between traditional understandings of the state and American constitutional government as it was framed in the eighteenth century, and the radically changing social and political-economic conditions of modern, late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century America. Amongst other things, Wilson focused extensively on the way that the country’s political and constitutional development had necessitated new understandings of the constitutional separation of powers, in a way that called for expanded national administrative capacities and a larger party and national leadership role for the modern presidency.

Selected by

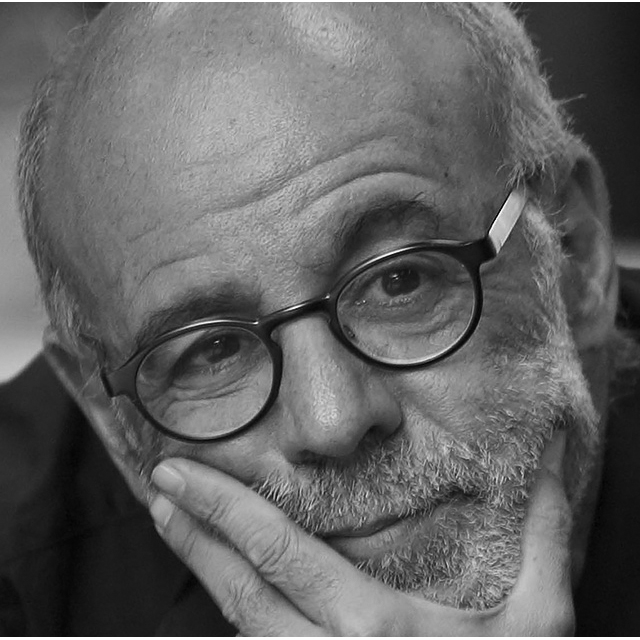

Ken I. Kersch

Professor of Political Science, at Boston College

William E. Forbath

Lloyd M. Bentsen Chair in Law, and Associate Dean for Research, The University of Texas at Austin School of Law

Document Excerpt

The makers of the Constitution constructed the federal government upon a theory of checks and balances which was meant to limit the operation of each part and allow to no single part or organ of it a dominating force; but no government can be successfully conducted upon so mechanical a theory. Leadership and control must be lodged somewhere; the whole art of statesmanship is the art of bringing the several parts of government into effective cooperation for the accomplishment of particular common objects, – and party objects at that….

The makers of the Constitution seem to have thought of the President as what the stricter Whig theorists wished the king to be: only the legal executive, the presiding and guiding authority in the application of the law and the execution of policy. His veto upon legislation was only his ‘check’ on Congress, – was a power of restraint, not of guidance. He was empowered to prevent bad laws, but he was not to be given an opportunity to make good ones. As a matter of fact he has become very much more. He has become the leader of his party and the guide of the nation in political purpose…

The role of party leader is forced upon the President by the method of his selection….As legal executive, his constitutional aspect, the President cannot be thought of alone. He cannot execute laws. Their actual daily execution must be taken care of by the several executive departments and by the now innumerable body of federal officials throughout the country…. [T]he President may be said to administer the presidency in conjunction with members of his cabinet, like the chairman of a commission…. Only the larger sort of executive questions are brought to him. Departments which run with easy routine and whose transactions bring few questions of general policy to the surface may proceed with their business for months and even years together without demanding his attention; and no department is in any sense under his direct charge. Cabinet meetings do not discuss detail; they are concerned only with the larger matters of policy or expediency which important business is constantly disclosing. There are no more hours in the President’s day than in another man’s…. [H]e must act almost entirely by delegation….

He cannot escape being the leader of his party except by incapacity and lack of personal force, because he is at once the choice of the party and of the nation. He is the party nominee, and the only party nominee for whom the whole nation votes…. No one else represents the people as a whole, exercising a national choice…. He is not so much part of its organization as its vital link of connection with the thinking nation. He can dominate his party by being spokesman for the real sentiment and purpose of the country, by giving direction to opinion, by giving the country at once the information and the statements of policy which will enable it to form its judgments alike of parties and of men. For he is also the political leader of the nation, or has it in his choice to be…. Let him once win the admiration and confidence of the country, and no other single force can withstand him, no combination of forces will easily overpower him. His position takes the imagination of the country….. He is the representative of no constituency, but of the whole people. When he speaks in his true character, he speaks for no special interest. If he rightly interpret the national thought and boldly insist upon it, he is irresistible; and the country never feels the zest of action so much as when its President is of such insight and calibre. Its instinct is for unified action, and it craves a single leader….

Some of our Presidents have deliberately held themselves off from using the full power they might legitimately have used, because of conscientious scruples, because they were more theorists than statesmen. They have held the strict literary theory of the Constitution, the Whig theory, the Newtonian theory…. But the makers of the Constitution … were statesman, not pedants….. The President is at liberty, both in law and conscience, to be as big a man as he can. His capacity will set the limit; and if Congress be overborne by him, it will be no fault of the makers of the Constitution, it will be from no lack of constitutional powers on its part, but only because the President has the nation behind him, and Congress has not…..