Historic Document

Commentaries on the Laws of England, vol. 1 The Rights of Persons (1765) and vol. 2, The Rights of Things (1766)

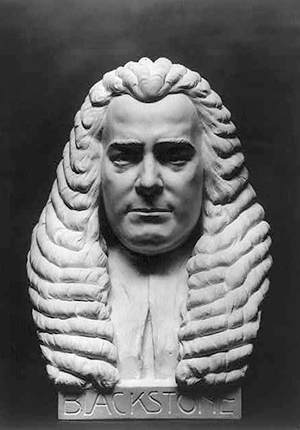

Sir William Blackstone | 1765 and 1766

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Divison

Summary

The federal system set up in the U.S. Constitution gave states control over the legal status of their residents, including women, the vast majority of whom were married and subject to a set of legal principles known as coverture. While, in general terms, coverture subsumed wives’ legal identities within those of their husbands and limited their ability to act legally in their own names, its specifics changed over time and differed from place to place, sometimes tightening, sometimes loosening. After the adoption of the U.S. Constitution, states not only kept existing laws in place, but then adopted the reimagined, restrictive definition of coverture laid out by Sir William Blackstone in his Commentaries on the Laws of England. While Blackstone’s version of coverture purported to express traditional practices, it selectively fashioned existing principles into a new synthesis that narrowed the legal prerogatives of wives. Published between 1765 and 1770, Blackstone’s Commentaries were widely read, admired, and applied in the new republic. Early American treatise writers used it as a model, copying out whole sections, including those on coverture, which they used to describe America’s laws for married women. From there, Blackstone’s version of coverture made its way into state laws and local practice.

Selected by

Laura F. Edwards

Class of 1921 Bicentennial Professor in the History of American Law and Liberty, and Professor of History at Princeton University

Kurt Lash

E. Claiborne Robins Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Richmond

Document Excerpt

By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband: under whose wing, protection, and cover, she performs everything; is said to be . . . under the protection and influence of her husband, her baron, or lord; and her condition during her marriage is called her coverture. Upon this principle, of an union of person in husband and wife, depend almost all the legal rights, duties, and disabilities, that either of them acquire by the marriage. . . . For this reason, a man cannot grant any thing to his wife, or enter into [contract] with her: the grant would be to suppose her separate existence; and to [contract] with her, would be only to [contract] with himself . . . .The husband is bound to provide his wife with necessaries [items necessary for subsistence] by law, as much as himself; and if she contracts debts for them, he is obliged to pay them; but for any thing besides necessaries, he is not chargeable. . . . If the wife be injured in her person or her property she can bring no action for redress without her husband’s concurrence, and in his name, as well as her own: neither can she be sued, without making the husband a defendant. . . . In criminal prosecutions, it is true, the wife may be indicted and punished separately . . . but, in trials of any sort, they are not allowed to be evidence for, or against each other; partly because it is impossible their testimony should be indifferent; but principally because of the union of person.

By marriage . . . [the property] which belonged formerly to the wife, are by act of vested in the husband, with the same degree of property and the same powers, as the wife, when [unmarried], had over them. This depends entirely on the notion of an unity of person between the husband and wife; it being held that they are one person in law . . . . And hence it follows, that whatever personal property belonged to the wife before marriage, is by marriage absolutely vested in the husband. In real estate, he only gains title to the rents and profits during coverture. . . . But, in [other property], the sole and absolute property vests in the husband, to be disposed of at his pleasure, if he chuses [sic] to take possession of them . . . .

The husband also (by the old law) might give his wife moderate correction. For as he is to answer for his misbehaviour, the law thought it reasonable to intrust him with this power of restraining her, by domestic chastisement, in the same moderation that a man is allowed to correct his servants or children; for whom the master or parent is also liable in some cases answer. . . . But, with us, in the politer reign of Charles the second, this power of correction began to be doubted. . . . Yet the lower rank of people, who were always fond of the old common law, still claim and exert their antient privilege: and the courts of law will still permit a husband to restrain a wife of her liberty, in case of any gross misbehavior.

These are the chief legal effects of marriage during the coverture; upon which we may observe, that even the disabilities, which the wife lied under, are for the most part intended for her protection and benefit. So great a favourite is the female sex of the laws of England.