Historic Document

Liberty of Contract (1909)

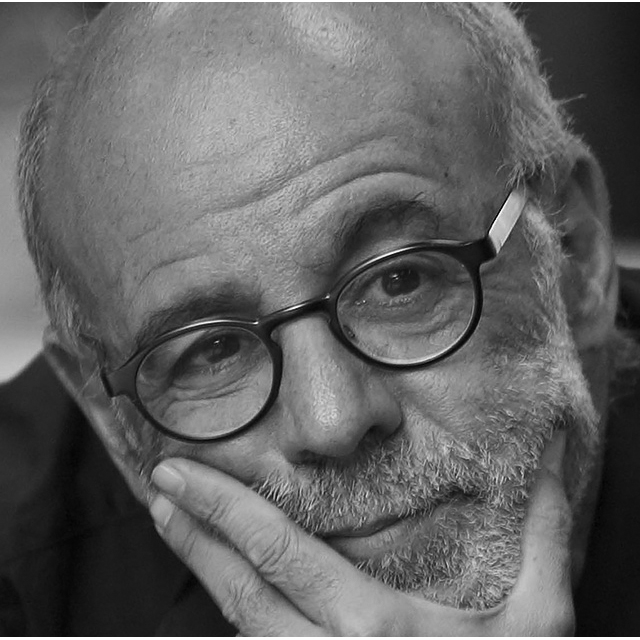

Roscoe Pound | 1909

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Summary

The Nebraska-born Dean of the Harvard Law School, and a pioneering scholar of the new “sociological jurisprudence” (which fed an emerging “Legal Realism”), Roscoe Pound was an omnipresent force advocating that legal scholars and professionals move beyond more formal and parochial understandings of law to assimilate law into the broader studies of history and society, especially the new social sciences. Rulings by judges finding a “liberty of contract” between employers and employees inherent in the due process clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments (and analogous provisions of state constitutions) to void regulations of employment contracts concerning matters such as minimum wages, maximum hours, payment in scrip, and unionization, were one of Pound’s major targets. Pound considered these rulings, and the liberty of contract doctrine which anchored them, exemplary cases of the distortions wrought by these misguided and antiquated understandings of law. These flawed understandings were now causing considerable damage to American society, and frustrating law’s adjustment to new social and political-economic conditions, and the law’s capacity advance the public interest, and provide the basis for meaningful individual freedom in a new industrial age.

Selected by

William E. Forbath

Lloyd M. Bentsen Chair in Law, and Associate Dean for Research, The University of Texas at Austin School of Law

Ken I. Kersch

Professor of Political Science, at Boston College

Document Excerpt

Why, then do courts persist in the fallacy [of the equality between the employer and employee agreeing to a contract for employment]? Why do so many of them force upon legislation an academic theory of equality in the face practical conditions of inequality? Why do we find a great learned court … taking the long step into the past of dealing with the relation between employer and employee … as if the parties were individuals—as if they were farmers haggling over the sale of a horse? Why is the conception of the relation of employer and employee so at variance with the common knowledge of mankind?

The late president has told us that it is because individual judges project their personal, social and economic views into the law. A great German publicist holds that it is because the party bent of judges has dictated decisions. But when a doctrine is announced with equal vigor and held with equal tenacity by courts of Pennsylvania and of Arkansas, of New York and of California, of Illinois and of West Virginia, of Massachusetts and of Missouri, we may not dispose of it so readily. Surely the sources of such a doctrine must lie deeper….

It is significant that the subject, so far as the form is concerned, is a new one…. The first decision turning upon it was rendered in 1886. The first extended discussion of the right of free contract as a fundamental natural right is in [Herbert] Spencer's Justice, written in 1891. The eighteenth century writers on natural law say nothing about it…..

The idea that unlimited freedom of making promises was a natural right came after enforcement of promises when made, had become a matter of course. It began as a doctrine of political economy, as a phase of Adam Smith’s doctrine which we commonly call laisser faire. It was propounded as a utilitarian principle of politics and legislation by [John Stuart] Mill. Spencer deduced it from his formula of justice. In this way it became a chief article in the creed of those who sought to minimize the functions of the state….

But we must remember that the task of the English individualists was to abolish a body of antiquated institutions that stood in the way of human progress. Freedom of contract was the best instrument at hand for the purpose. They adopted it as a means, and made it an end….

In my opinion, the causes to which we must attribute the course of American constitutional decisions upon liberty of contract are seven: (1) The currency in juristic thought of an individualist conception of justice, which exaggerates the importance of property and of contract, exaggerates private right at the expense of public right, and is hostile to legislation, taking a minimum of law-making to be the ideal; (2) what I have ventured to call … a condition of mechanical jurisprudence a condition of juristic thought and judicial action in which deduction from conceptions has produced a cloud of rules that obscures the principles from which they were drawn, in which conceptions are developed logically at the expense of practical results and in which the artificiality characteristic of legal reasoning is exaggerated; (3) the survival of purely juristic notions of the state and of economics and politics as against the social conceptions of the present; (4) the training of lawyers in eighteenth century philosophy of law and the pretended contempt for philosophy in law that keeps the legal profession in the bonds of the philosophy of the past because it is to be found in law-sheep bindings; (5) the circumstance that natural law is the theory of our bills of rights and the impossibility of applying such a theory except when all men are agreed in their moral and economic views and look to a single authority to fix them; (6) the circumstance that our earlier labor legislation … came before the public was prepared for it, so that the courts largely voiced well-meant but unadvised protests of the old order against the new, at a time when the public at large was by no means committed to the new; and (7) by no means least, the sharp line between law and fact in our legal system which requires constitutionality, as a legal question, to be tried by artificial criteria of general application and prevents effective judicial investigation or consideration of the situations of fact behind or bearing upon the statutes….

Suffice it to say here that the doctrine as to liberty of contract is bound up in the decisions of our courts with a narrow view of what constitutes special legislation or class legislation that greatly limits effective law-making. If we can only have laws of wide generality of application, we can have only a few laws; for the wider their application the more likelihood there is of injustice in concrete cases. But from the individualist standpoint a minimum of law is desirable. The common law antipathy to legislation sympathizes with this, and in consequence we find courts saying that it is not necessary to consider the reasons that led up to the type of legislation they condemn and that the maxim that the government governs best which governs least is proper for courts to bear in mind in expounding the Constitution….

An acute and well-informed observer [Jane Addams] said recently: “From my own experience, I should say, perhaps, that the one symptom among workingmen which most definitely indicates a class feeling, is a growing distrust of the integrity of the courts, the belief that the present judge has been a corporation attorney, that his sympathies and experience and his whole view of life is on the corporation side.” The attitude of many of our courts on the subject of liberty of contract is so certain to be misapprehended, is so out of the range of ordinary understanding, the decisions themselves are so academic and so artificial in their reasoning, that they cannot fail to engender such feelings. Thus, those decisions do an injury beyond the failure of a few acts. These acts can be replaced as legislatures learn how to comply with the letter of the decisions and to evade the spirit of them. But the lost respect for courts and law cannot be replaced. The evil of those cases will live after them in impaired authority of the courts long after the decisions themselves are forgotten.