Historic Document

Remarks on Direct Election of Senators (1892)

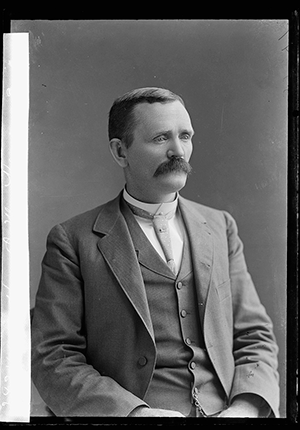

Omer Kem | 1892

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, C. M.Bell Studio Collection

Summary

The original Constitution gave state legislatures the power to choose senators. In 1913, the Seventeenth Amendment uprooted this indirect system and provided for the direct popular election of senators. The Progressive Era (roughly 1896-1916) marked a moment of sustained and significant formal changes in the Constitution second only to the two moments of constitutional change that brought us the Bill of Rights and the Reconstruction Amendments. The Seventeenth Amendment resembled its Progressive Era cousins (the Sixteenth, Eighteenth, and Nineteenth Amendments) in this: Each shifted power toward the federal government and away from the states; and each was the outgrowth of longstanding and overlapping reform movements.

The Seventeenth sprang from Populist roots and arguments that sounded in political economy. Its advocates contended that too many state legislatures had become pawns of corporate power; and that the Senate they chose was a “millionaires’ club” that no longer represented the people. Populist representative Omer Kem, from the western plains of Nebraska, and reportedly the first person elected to Congress who had lived in a sod house, made the Populist case in characteristic terms.

Selected by

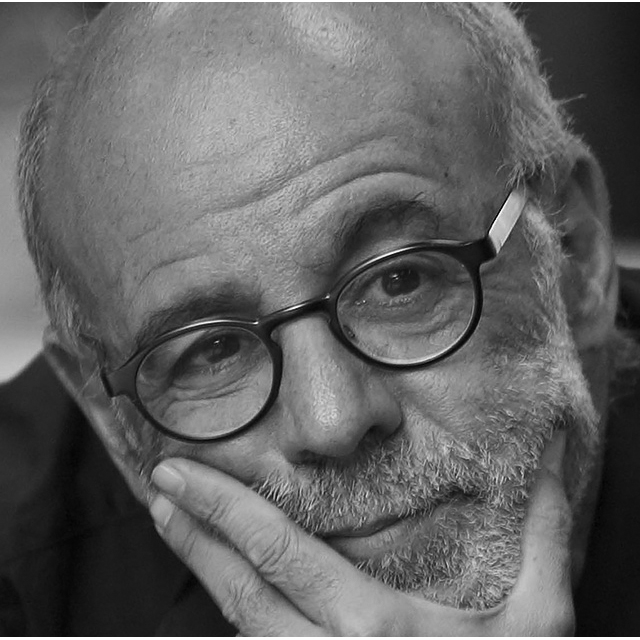

William E. Forbath

Lloyd M. Bentsen Chair in Law, and Associate Dean for Research, The University of Texas at Austin School of Law

Ken I. Kersch

Professor of Political Science, at Boston College

Document Excerpt

Mr. Chairman, in speaking to the resolution that is before the House for its consideration at this time, I do not do so believing it a cure for all the evils complained of by the people. But I regard it as a step in the direction of popular government, in which the voice of the whole people will not only be heard, but heeded. In it lies a principle of justice and equality that should be better established by the Constitution—a principle that must be well established and maintained or we cannot hope to preserve that perfect liberty given by the Creator as the birthright of man. . . .

[G]eneral discontent prevails throughout our land among those who produce its wealth. The result, as we believe, Mr. Chairman, of false and evil systems that have crept in through defects in the Constitution, by which the natural rights of the people have been taken from them, resulting in an unequal distribution of the wealth of the country, by which it is fast becoming aggregated in the hands of the few, and, if continued, must inevitably result in wiping out the great middle class entirely and the establishment of the two extremes; the extremely poor and extremely wealthy, landlord and tenant, aristocrat, and plebian. . . .

Mr. Chairman, the resolution now pending embodies a question of vital importance, and it ought to receive the earnest, unbiased better thought of every member on this floor, for in it is the principle that will alone secure the perpetuity of the Government itself. The right of the majority to rule, is the chief corner stone of the structure of our Government, and yet, strange to say, concealed in its organic law are the elements of its own destruction, and by which, this principle has time and again been trampled under the feet of the heartless, soulless, partisan, office seeker, the desires of the people disregarded, and their expressed will outraged.

Therefore, I believe the time has fully come when the people should be allowed to say in the method provided for in the resolution whether the present manner of electing United States Senators shall continue, or whether they shall be elected as the members of the House are elected, and compelled to give an account of their stewardship directly to the people whom they are supposed to serve. . . .

Mr. Chairman, I am on the side of the people in this unequal contest. I therefore support this resolution that seeks to change a system that is unquestionably on the side of the dollar and against the people permitting a few to cast the votes of the millions, thereby making it possible for the wealthy corporations and trusts to purchase votes sufficient to place an unscrupulous pliant tool in the United States Senate that would do their bidding and seek to influence legislation in their interests, giving them privileges and advantages over others that no one can have without violating the first principles of government. . . .

It is quite possible for those who have their million to bribe one, five, ten or twenty votes even in order to accomplish their ends, but it is not possible to bribe a whole State, hence the wisdom of adopting the popular vote in electing all legislative officers.