Historic Document

Address of Mr. Justice Field, The Centenary of the Supreme Court (1890)

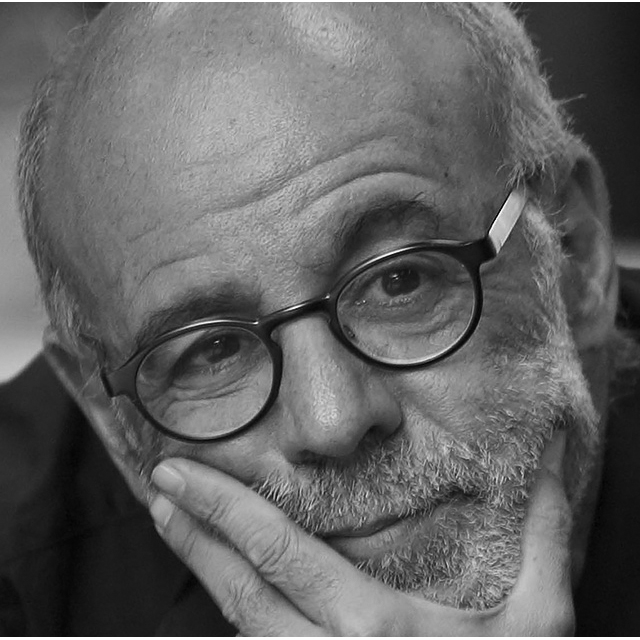

Stephen J. Field | 1890

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Brady-Handy photograph collection

Summary

The Massachusetts-born Field, who went west to California as part of the 1849 Gold Rush but soon turned towards a prominent career in law and politics, was appointed by Abraham Lincoln to the Supreme Court as Unionist Democrat. Justice Stephen J. Field emerged as one of the most insistent early proponents of the view that the Constitution, perhaps most significantly, as the Court’s doctrine developed, in the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, provided stringent, and unalienable, national guarantees for fundamental rights, whether express in the text or implied, especially for foundational rights concerning property upon which, Field held, all other freedoms were premised. Field was disturbed by emerging efforts of reformers in an increasingly democratized polity concerned with emerging inequalities of wealth and political power to limit these rights in the ostensible interest of the common good through regulation and redistribution. He repeatedly urged judges to stiffen their spines to resist these disturbing trends, and stand up to protect what he regarded as these inalienable constitutional rights.

Selected by

William E. Forbath

Lloyd M. Bentsen Chair in Law, and Associate Dean for Research, The University of Texas at Austin School of Law

Ken I. Kersch

Professor of Political Science, at Boston College

Document Excerpt

In every age and with every people there have been celebrations for triumphs in war … and for triumphs of peace …. But never until now has there been in any country a celebration like this, to commemorate the establishment of a judicial tribunal as a co-ordinate and permanent branch of its government…. This celebration had its inspiration in a profound reverence for the Constitution of the United States … and the conviction that this tribunal has materially contributed to its just appreciation and to a ready obedience to its authority….

Experience has shown that in a country of great territorial extent and varied interests, peace and lasting prosperity can exist with a civilized people only when local affairs are controlled by local authority, and at the same time there are lodged in the general government of the country such sovereign powers as will enable it to regulate the intercourse of its people with foreign nations and between the several communities, protect them in all their rights in such intercourse, defend the country against invasion and domestic violence, and maintain the supremacy of the laws throughout its whole domain. This principle the framers of the Constitution acted upon in establishing the government of the Union, by leaving unimpaired the power of the States to control all matters of local interest, and creating a new governing of sovereign powers for matters of general and national concern…. The prosperity which has followed this distribution of governmental powers not only attests the wisdom of the framers of the Constitution, but transcends even their highest expectations. In the history of no people – ancient or modern – has anything been known at all comparable….

[The U.S. Supreme Court’s power of judicial review] is sometimes characterized by foreign writers and jurists as a unique provision of a disturbing and dangerous character, tending to defeat the popular will as expressed by the legislature….The limitations upon legislative power, arising from the nature of the Constitution and its specific restraints in favor of private rights, cannot be disregarded without conceding that the legislature can change at will the form of our government from one of limited to one of unlimited powers….

As population and wealth increase – as the inequalities in the conditions of men become more and more marked and disturbing – as the enormous aggregation of wealth possessed by some corporations excites uneasiness lest their power should become dominating in the legislation of the country, and thus encroach upon the rights or crush out the business of individuals of small means – as population in some quarters presses upon the means of subsistence, and angry menaces against order find vent in loud denunciations – it becomes more and more the imperative duty of the Court to enforce with a firm hand every guarantee of the Constitution…. It should never be forgotten that protection to property and to persons cannot be separated. Where property is insecure, the rights of persons are unsafe….

[I]t is not sufficient for the performance of his judicial duty that a judge should act honestly in all that he does. He must be ready to act in all cases presented for his judicial determination with absolute fearlessness…. To decide against his conviction of the law or judgment as to the evidence, whether moved by prejudice or passion, or the clamor of the crowd, is to assent to a robbery as infamous in morals and as deserving of punishment as that of the highwayman or the burglar; and to hesitate or refuse to act when duty calls is hardly less the subject of just reproach. If he is influenced by apprehensions that his character will be attacked, or his motives impugned, or that this judgment will be attributed to the influence of particular classes, cliques or associations, rather than to his own convictions of the law, he will fail lamentably in his high office.