Historic Document

The Virginia Resolutions (1798)

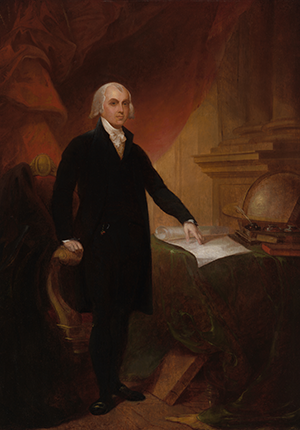

James Madison | 1798

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Gift of Frederic Edwin Church)

Summary

In 1798, President John Adams signed into law the federal Sedition Act, which criminalized the publication of any “false, scandalous, or malicious writing” against the government of the United States. In response, James Madison and Thomas Jefferson anonymously drafted, respectively, the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions which were read and adopted by the Virginia and Kentucky state assemblies. The Resolutions became a rallying cry for political opposition and helped secure Thomas Jefferson’s victory in the elections of 1800. Madison’s Virginia Resolutions and its “compact theory” of the federal Constitution was one of the most influential statements regarding the nature of the federal Constitution issued prior to the Civil War. The Virginia Resolution’s invocation of the fundamental rights of speech and press continues to inform the modern Supreme Court’s interpretation of the First Amendment.

Selected by

Laura F. Edwards

Class of 1921 Bicentennial Professor in the History of American Law and Liberty, and Professor of History at Princeton University

Kurt Lash

E. Claiborne Robins Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Richmond

Document Excerpt

Resolved, that the General Assembly of Virginia . . . doth explicitly and peremptorily declare, that it views the powers of the federal government, as resulting from the compact to which the states are parties; as limited by the plain sense and intention of the instrument constituting that compact; as no farther valid than they are authorised by the grants enumerated in that compact, and that in case of a deliberate, palpable and dangerous exercise of other powers not granted by the said compact, the states who are parties there-to have the right, and are in duty bound, to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining within their respective limits, the authorities, rights and liberties appertaining to them.

. . .

That the General Assembly doth particularly protest against the palpable and alarming infractions of the constitution, in the two late cases of the “alien and sedition acts,” passed at the last session of Congress; the first of which exercises a power no where delegated to the federal government; and which by uniting legislative and judicial powers, to those of executive, subverts the general principles of free government, as well as the particular organization and positive provisions of the federal constitution: and the other of which acts, exercises in like manner a power not delegated by the constitution, but on the contrary expressly and positively forbidden by one of the amendments thereto; a power which more than any other ought to produce universal alarm, because it is levelled against that right of freely examining public characters and measures, and of free communication among the people thereon, which has ever been justly deemed, the only effectual guardian of every other right.

. . .

[T]he General Assembly doth solemnly appeal to the like dispositions of the other States, in confidence that they will concur with this Commonwealth in declaring, as it does hereby declare, that the acts aforesaid are unconstitutional, and that the necessary and proper measures will be taken by each, for cooperating with this State in maintaining unimpaired the authorities, rights, and liberties, reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.