Historic Document

The Promise of American Life (1909)

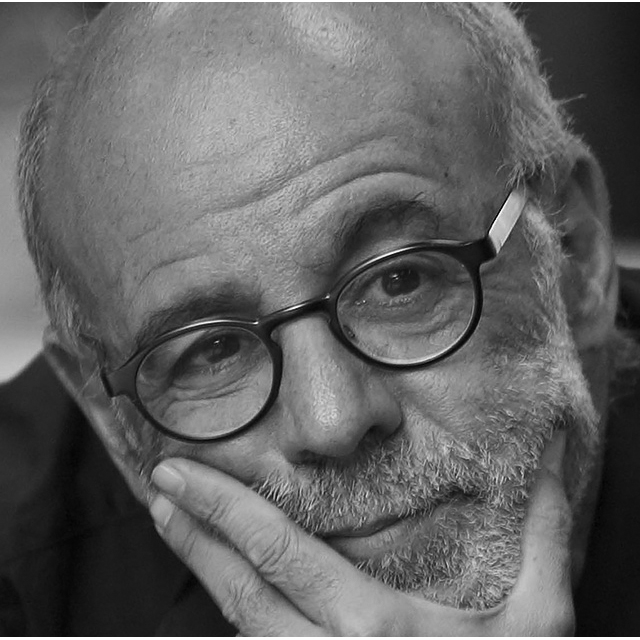

Herbert Croly | 1909

University of Toronto, Robarts Library

Summary

The New York journalist Herbert Croly, founder of the flagship progressive magazine The New Republic, was one of the leading intellectual lights of the early twentieth century progressive movement. In his defining statement The Promise of American Life, Croly argued for the inadequacy of both the Jeffersonian constitutional tradition of weak national government and the Hamiltonian vision of strong national government, which Croly favored. Both, he contended, had been corrupted by a disposition in favor of the country’s privileged economic classes. As such, neither was sufficient on its own terms to guide the country forward as it faced the political-economic challenges of the new twentieth century arising out of unprecedented concentrations of private economic power and economic and political privilege. Croly explicated a new synthesis that would enlist the Hamiltonian means of a powerful interventionist national government, underwritten by the commonality of a national democratic political community committed to the national interest, to realize, under the new conditions, the Jeffersonian ends of equal liberty and equal opportunity for all under law. Croly’s statement and program caught the eye of Theodore Roosevelt, who used it as the basis for his “New Nationalist” progressivism.

Selected by

William E. Forbath

Lloyd M. Bentsen Chair in Law, and Associate Dean for Research, The University of Texas at Austin School of Law

Ken I. Kersch

Professor of Political Science, at Boston College

Document Excerpt

A numerous and powerful group of reformers has been collecting whose whole political policy and action is based on the conviction that the “common people” have not been getting the Square Deal to which they are entitled under the American system…. A considerable proportion of the American people is beginning to exhibit economic and political, as well as personal discontent…. Unless the great majority of Americans not only have, but believe they have a fair chance, the better American future will be dangerously compromised…. [A] more highly socialized democracy is the only practical substitute on the part of convinced democrats for an excessively individualized democracy….

All our histories recognize … the existence from the very beginning of our national career of two different and, in some respects, antagonistic groups of political ideas… represented by Jefferson, and … by Hamilton. It is very generally understood … that neither the Jeffersonian nor the Hamiltonian doctrine was entirely adequate, and that in order to reach a correct understanding of … the complex of American national life, a combination must be made of both Republicanism and Federalism…. I do not believe that it has ever been mixed in just the proper proportions…. [W]e must seek to discover wherein each of these sets of ideas was right, and wherein each was wrong…. I shall not disguise the fact that, on the whole, my own preferences are on the side of Hamilton rather than Jefferson….

The difference between them was really less a difference of purpose than of the means whereby a purpose should be accomplished…. [A] system of checks and balances … was calculated to thwart the popular will, just in so far as that will did not conform to what the Federalists believe to be the essentials of a stable political and social order. It was antagonistic to democracy …. [T]his was at once a grave error on their part and a grave misfortune for the American state…. Moreover, the radical American democrats were doing much to deserve the misgivings of the Federalists. Their ideas were narrow, impractical, and hazardous….

The Constitution was the expression not only of a political faith, but also of political fears…. [Individual and state rights] had their value in American national history…. It remains none the less true, however, that every popular government should in the end, and after necessarily prolonged deliberation, possess the power of taking any action, which, in the opinion of a decisive majority of the people, is demanded by the public welfare. Such is not the case with the government organized under the Federal Constitution…. A very small percentage of the American people can … permanently thwart the will of an enormous majority, and there can be no justification for such a condition on any possible theory of popular Sovereignty.

Underlying … Hamilton’s policy can be discerned a definite theory of governmental functions. The central government is to be used, not merely to maintain the Constitution, but to promote the national interest …. Hamilton saw clearly that the American Union was far from being achieved when the Constitution was accepted by the states and the machinery of the Federal government was set in motion…. [B]ut [unfortunately] he did not seek a sufficiently broad, popular basis for the realization of those ideas. He was betrayed by his fears and by his lack of faith …. He succeeded in imbuing both men of property and the mass of the “plain people” with the idea that the well-to-do were the peculiar beneficiaries of the American federal organizations, the result being that the rising democracy came more than ever to distrust the national government….

Reform is … meaningless and powerless unless the Jeffersonian principle of non-interference is abandoned …. [T]he automatic harmony of the individual and the public interest, which is the essence of the Jeffersonian democratic creed, has proved to be an illusion…. In reviving the practice of vigorous national action for the achievement of a national purpose, the better reformers have, if they only knew it, been looking in the direction of a much more trustworthy and serviceable political principle. The assumption of such a responsibility implies the rejection of a large part of the Jeffersonian creed, and a renewed attempt to establish in its place the popularity of its Hamiltonian rival. On the other hand, it involves no less surely the transformation of Hamiltonianism into a thoroughly democratic political principle….. When a people are being nationalized, their political, economic, and social organization or policy is being coordinated with their actual needs and their moral and political ideals….