Historic Document

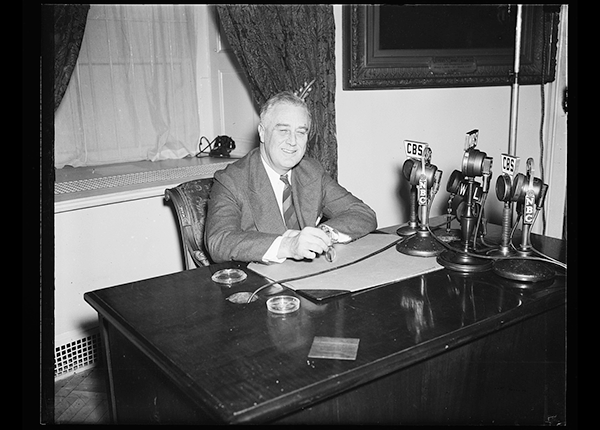

Address on Constitution Day (1937)

Franklin Delano Roosevelt | 1937

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, photograph by Harris & Ewing

Summary

The Great Depression of the 1930s saw an epochal battle between President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Supreme Court. On one side, FDR and the New Dealers saw the need for a national government empowered to regulate and reform a broken economy, boosting wages and guaranteeing the economic security of ordinary Americans via social insurance and government protection of union organizing and collective bargaining rights. Such measures were not merely allowable, said Roosevelt; they were constitutional duties. On the other side, a majority of the Court, supported by the Republican Party and most of the business community, held that the Constitution sharply restrained the role of government, in favor of private industry, employers, and states’ rights. As the Supreme Court struck down key New Deal programs, FDR hailed the Democrats’ landslide victory in the 1936 elections as a mandate “to save the Constitution from the Court and the Court from itself.” In February 1937, he introduced his controversial “court-packing plan,” which would have added six new Justices to the Court, and ensured a pro-New Deal majority. Within a few months of FDR’s threat, the Court made a dramatic about-face, upholding New Deal reforms everyone expected it to strike down. It was the “switch in time that saved Nine.” The plan was buried, but no more New Deal measures would be invalidated. In this Fall 1937 Constitution Day Address, the President looks back.

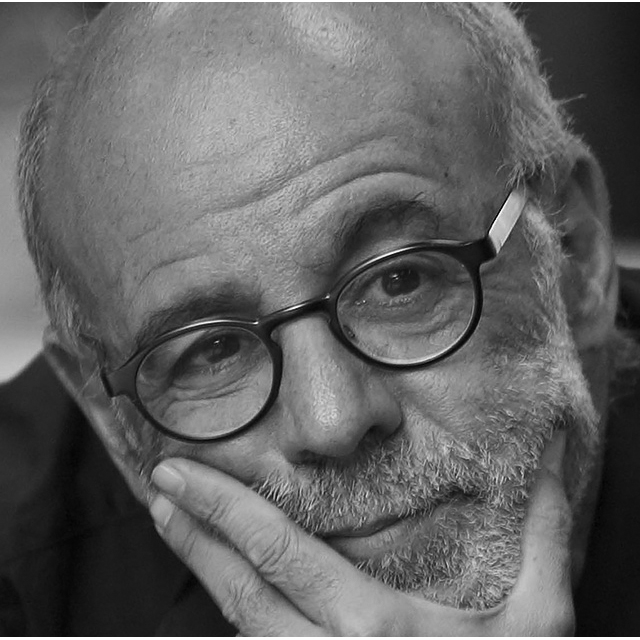

Selected by

William E. Forbath

Lloyd M. Bentsen Chair in Law, and Associate Dean for Research, The University of Texas at Austin School of Law

Ken I. Kersch

Professor of Political Science, at Boston College

Document Excerpt

The Constitution of the United States was a layman’s document, not a lawyer’s contract. That cannot be stressed too often. Madison, most responsible for it, was not a lawyer; nor was Washington or Franklin, whose sense of the give-and-take of life had kept the Convention together.

This great layman’s document was a charter of general principles, completely different from the “whereases” and the “parties of the first part” and the fine print which lawyers put into leases and insurance policies and installment agreements.

When the Framers were dealing with what they rightly considered eternal verities, unchangeable by time and circumstance, they used specific language. In no uncertain terms, for instance, they forbade titles of nobility, the suspension of habeas corpus and the withdrawal of money from the Treasury except after appropriation by law. With almost equal definiteness they detailed the Bill of Rights.

But when they considered the fundamental powers of the new national government they used generality, implication and statement of mere objectives, as intentional phrases which flexible statesmanship of the future, within the Constitution, could adapt to time and circumstance. For instance, the Framers used broad and general language capable of meeting evolution and change when they referred to commerce between the States, the taxing power and the general welfare.

Even the Supreme Court was treated with that purposeful lack of specification. Contrary to the belief of many Americans, the Constitution says nothing about any power of the Court to declare legislation unconstitutional; nor does it mention the number of judges for the Court . . . . Clearly a majority of the delegates believed that the relation of the Court to the Congress and the Executive, like the other subjects treated in general terms, would work itself out by evolution and change over the years.

But for one hundred and fifty years we have had an unending struggle between those who would preserve this original broad concept of the Constitution as a layman’s instrument of government and those who would shrivel the Constitution into a lawyer’s contract.

. . .

You will find no justification in any of the language of the Constitution for delay in the reforms which the mass of the American people now demand.

. . .

On this solemn anniversary I ask that the American people rejoice in the wisdom of their Constitution.

I ask that they guarantee the effectiveness of each of its parts by living by the Constitution as a whole.

I ask that they have faith in its ultimate capacity to work out the problems of democracy, but that they justify that faith by making it work now rather than twenty years from now.

I ask that they give their fealty to the Constitution itself and not to its misinterpreters.

I ask that they exalt the glorious simplicity of its purposes, rather than a century of complicated legalism.

I ask that majorities and minorities subordinate intolerance and power alike to the common good of all.

For us the Constitution is a common bond, without bitterness, for those who see America as Lincoln saw it, “the last, best hope of earth.”

So we revere it, not because it is old but because it is ever new, not in the worship of its past alone but in the faith of the living who keep it young, now and in the years to come.