Historic Document

Remarks on the Review of the Controversy Between Great Britain and Her Colonies (1771)

Edward Bancroft | 1771

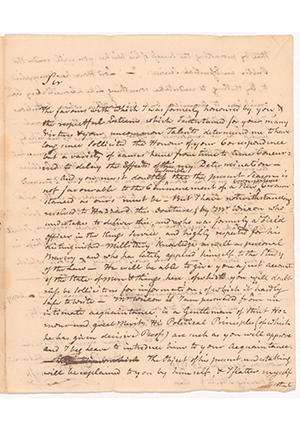

Samuel Adams papers, The New York Public Library

Summary

Bancroft’s pamphlet, while not well-known today, was enormously influential in its day. Written from London to answer a leading defense of Parliamentary sovereignty—William Knox’s The Controversy Between Great Britain and Her Colonies Reviewed—Bancroft’s was the first piece of American writing to articulate what is now called the dominion theory: the view that the colonies were outside Parliament’s lawmaking jurisdiction but connected to the empire through their common allegiance to the British King. Based on a detailed reading of seventeenth-century English and colonial history—of the settlement of the colonies, of the original charters, and of the struggle between the Stuart monarchs and the Houses of Parliament—Bancroft helped answer the most difficult question the colonists faced to that point: How could they be English subjects, entitled to the requisite rights and protections, yet simultaneously exempt from Parliament’s sovereign lawmaking authority? Technically, he was not the first to articulate this position (James Wilson had done so as early as 1768, but did not publish those reflections until 1774), but in first making the case publicly, Bancroft provided a template that became the foundation of so much patriot resistance literature in the years to come, including Thomas Jefferson’s A Summary View of the Rights of British America and Alexander Hamilton’s The Farmer Refuted. Bancroft’s writing would prove so influential that Thomas Hutchinson, the infamous royal governor of Massachusetts, in his extended debate with members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1773 over the nature of sovereignty in the British Empire, complained that they had all been led astray by Bancroft’s pesky pamphlet.

Selected by

William B. Allen

Emeritus Dean of James Madison College and Emeritus Professor of Political Science at Michigan State University

Jonathan Gienapp

Associate Professor of History at Stanford University

Document Excerpt

The first Settlers in the American Colonies, at the Time of their Migration, besides their natural Right to Freedom, were constitutionally intitled to all the Rights, Privileges, and Immunities of Englishmen; and the Security and Perpetuation of these, or similar Privileges, was, in forming the Constitution of the Colonies, expresly stipulated, between the king and people, and confirmed by the faith of the Royal Charters; fundamental, and consequently indefeasible Acts, equally binding on the Prince and Subjects; and I will venture to assert, that neither Great Britain, not any other Nation, has a better Title to its Constitution, than that of the Colonies. …

[T]he first inhabitants of our Colonies having a just Right to separate themselves, and the King a Constitutional Right to permit them to separate themselves, from the Community, and having granted them an Accession of foreign Territory, which he had a legal right to alienate for ever from the Crown and Realm, even to Foreigners, what Law or Principle in the English Constitution, forbids their retiring to the Territories so granted in America, and there, by the Consent of their Sovereign, becoming distinct States, on the Terms and Privileges stipulated between their Kind and themselves? Whoever places the Settlement of the Colonies in this just Point of View, will immediately discover the Fallacy of all those Arguments which have been objected to the Power of the Crown, in granting their Inhabitants an Emancipation from the Authority of Parliament.—As long as they continued within the Realm as a collective Part of its Inhabitants, and received Protection from its Laws and Government, no Power whatever could possibly exempt them from Obedience to its Legislative Authority: But this Obligation to Obedience necessarily depended on the Term of their Continuance within the Community, and naturally ceased on their Separation from it; and though the King’s prerogative extends, indiscriminately, to all States owning him Allegiance, yet the Legislative Power of each State, if the People have any Share therein, is necessarily confined within the State itself, it being repugnant to the Laws of Nature and Nations for the Subjects of on State to exercise Jurisdiction over those of another: The People being allowed to participate the Legislative Authority, thereby to preserve their own Freedom. …

After this Review of the most important Transactions relating to the most ancient of our Colonies…I have sufficiently demonstrated that James and Charles, by whose Authority they were settled, had a Constitutional Right to grant the first Settlers their Title to the Territories in America, with all the powers of distinct Legislation and Government…nothing more was necessary to constitute the Independency of the Colonies, since if their first Inhabitants received and settled those Countries, on the Terms of independent Legislation and Government, made by those who had a legal right to grant these Terms, it is self-evident that no Power whatever could afterwards unite them to the Realm of England, without their formal and express Consent, which has never been given, nor have they ever been considered as within this Kingdom. …

If, however, I could believe it possible to unite Great Britain and the colonies, equally and justly, in a legislative Capacity, and overcome those insuperable Obstacles which Nature has interposed to this Union, I would endeavour to promote it by every honest Expedient, as the surest Method of securing their Stability and Happiness, instead of citing Facts to prove the Right of the latter to the Privileges of distinct Legislation and Government; but as I cannot believe this practicable, and as I well know, that it is incompatible with their Freedom, and repugnant to the Spirit of the British Constitution, to live in Subjection to the Laws of an Assembly in which they have no Representation, I have thought it my Duty thus to explain their original State and Constitution.