Historic Document

Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break the Silence (1967)

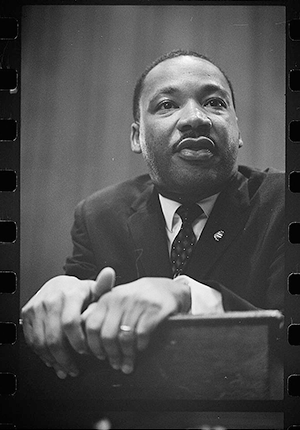

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. | 1967

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, U.S. News & World Report Magazine Collection

Summary

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was a Black church leader and minister, political philosopher, and activist who was one of the most prominent leaders of the civil rights movement. He had been laboring for several years to bring his Southern nonviolent protests to bear on national questions such as poverty, housing, and employment when he chose to deliver this high-profile speech criticizing the Vietnam War at Riverside Church in New York City in 1967. The immediate response to the speech, from many political and civic figures who had sympathized with King’s previous advocacy, was strongly negative. King, however, continued to speak out against the war, in line with his commitment to nonviolence both in the antiwar effort and in his fight for the civil rights of Black Americans.

Selected by

Christopher Brooks

Professor of History, East Stroudsburg University

Kenneth Mack

Lawrence D. Biele Professor of Law, Harvard Law School

Document Excerpt

. . . There is at the outset a very obvious and almost facile connection between the war in Vietnam and the struggle I and others have been waging in America. A few years ago there was a shining moment in that struggle. It seemed as if there was a real promise of hope for the poor, both black and white, through the poverty program. . . . Then came the buildup in Vietnam, and I watched this program broken and eviscerated as if it were some idle political plaything of a society gone mad on war. And I knew that America would never invest the necessary funds or energies in rehabilitation of its poor so long as adventures like Vietnam continued to draw men and skills and money like some demonic, destructive suction tube. . . .

. . . [W]e have been repeatedly faced with the cruel irony of watching Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools. So we watch them in brutal solidarity burning the huts of a poor village, but we realize that they would hardly live on the same block in Chicago. . . .

My third reason . . . grows out of my experience in the ghettos of the North over the last three years, especially the last three summers. As I have walked among the desperate, rejected, and angry young men, I have told them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems. . . . They asked if our own nation wasn’t using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, to bring about the changes it wanted. Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today: my own government. . . .

. . . But even if it were not present, I would yet have to live with the meaning of my commitment to the ministry of Jesus Christ. To me, the relationship of this ministry to the making of peace is so obvious that I sometimes marvel at those who ask me why I am speaking against the war. Could it be that they do not know that the Good News was meant for all men—for communist and capitalist, for their children and ours, for black and for white, for revolutionary and conservative? . . .

They watch as we poison their water, as we kill a million acres of their crops. They must weep as the bulldozers roar through their areas preparing to destroy the precious trees. They wander into the hospitals with at least twenty casualties from American firepower for one Vietcong-inflicted injury. So far we may have killed a million of them, mostly children. . . .

Here is the true meaning and value of compassion and nonviolence, when it helps us to see the enemy’s point of view, to hear his questions, to know his assessment of ourselves. . . .

I am convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin, we must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered. . . .

This call for a worldwide fellowship that lifts neighborly concern beyond one’s tribe, race, class and nation is in reality a call for an all-embracing and unconditional love for all mankind. . . .

If we will make the right choice, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our world into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. If we will but make the right choice, we will be able to speed up the day, all over America and all over the world, when justice will roll down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.