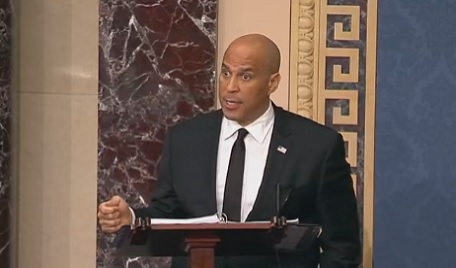

On April 1, 2025, Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey set a record for making the longest speaking appearance on the Senate floor. But Booker’s effort did not likely qualify as a “filibuster,” one of the chamber’s unique traditions of attempting to block or delay a vote by not allowing debate on it to end.

Around 7 p.m. EDT on March 31, Senator Booker took the floor as the Senate considered the nomination of Matthew Whitaker as the ambassador to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Booker spoke at length against the Trump administration, occasionally pausing to answer lengthy questions posed by other senators. He stopped talking on the floor at 8:06 p.m. on April 1, with his total floor speech length timed at 25 hours and 4 minutes.

Around 7 p.m. EDT on March 31, Senator Booker took the floor as the Senate considered the nomination of Matthew Whitaker as the ambassador to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Booker spoke at length against the Trump administration, occasionally pausing to answer lengthy questions posed by other senators. He stopped talking on the floor at 8:06 p.m. on April 1, with his total floor speech length timed at 25 hours and 4 minutes.

Previously, Senator Strom Thurmond held the record for the longest floor appearance when he held the Senate floor for 24 hours and 18 minutes while speaking against the Civil Rights Act of 1957. Thurmond had tried to launch a filibuster to block the law, which the Senate passed despite his efforts.

With Booker’s efforts concluded, a public debate started about whether his marathon appearance should count as a true filibuster, or instead as just a long speaking appearance. Most likely, based on the rules of the Senate and tradition, Booker’s efforts will count as the latter, and not as included in the list of classic Senate filibusters.

The tradition of lengthy speeches goes far back in the Senate’s history. The Senate’s website defines a filibuster as “a loosely defined term for action designed to prolong debate and delay or prevent a vote on a bill, resolution, amendment, or other debatable question.” The Congressional Research Service has a slightly different definition: “Filibustering includes any use of dilatory or obstructive tactics to block a measure by preventing it from coming to a vote.”

In 1917, the Senate started to rein in lengthy speaking appearances by passing Senate Rule XXII and introducing the concept of the “cloture” rule, following a public backlash against a filibuster from 11 senators that prevented the arming of merchant ships on the eve of World War I.

The Senate’s cloture rule at first allowed two-thirds of the members present and voting on Senate the floor to end floor debate by voting on a motion limiting speaking times for senators. Over time, the cloture requirement fell to three-fifths of the members, and then to a simple majority for some votes, including approving the nomination of ambassadors by the president.

On March 31, 2025, the Senate voted to invoke cloture for the nomination vote for Whitaker as NATO ambassador. In a 49-42 vote, Democratic Senator Jeanne Shaheen of New Hampshire joined the Republican caucus in setting a 30-hour time limit for debate after the cloture vote on the Whitaker nomination before it went for a vote in front of the full Senate.

Booker then took the floor and followed the same rules that apply to filibustering, which required him to speak at various intervals, entertain very long questions, not leave his desk area, and not depart the Senate floor, even to use the Senate’s bathroom facilities.

However, since the Senate had invoked cloture, Booker could not block or obstruct the vote on Whitaker’s nomination from happening, which is one of the key goals of any filibuster. His lengthy appearance may have delayed the vote, which some people could consider as meeting part of the broad Senate website definition of a filibuster.

But other definitions concur with the idea that the goal of the filibuster is to try to stop a vote from happening. Merriam-Webster defines a filibuster as “the use of delaying tactics (as long speeches) to put off or prevent action especially in a legislative assembly.” And Black’s Law Dictionary defines a filibuster as “a dilatory tactic, esp. prolonged and often irrelevant speechmaking employed in an attempt to obstruct legislative action.”

Regardless, Senator Booker now holds the record for the longest speech in Senate history.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.