On April 15, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln died from his assassin’s wounds. But if John Wilkes Booth’s plot were entirely successful, a little-known Senator may have been thrust into the White House.

Booth’s full plot included killing Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson, and Secretary of State William Seward. General Ulysses Grant was another possible target. But only two attacks took place on April 14, 1865, with Seward surviving an assassination attempt and Lincoln dying from Booth's single gunshot.

Booth’s full plot included killing Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson, and Secretary of State William Seward. General Ulysses Grant was another possible target. But only two attacks took place on April 14, 1865, with Seward surviving an assassination attempt and Lincoln dying from Booth's single gunshot.

According to the rules of presidential succession in 1865, only Vice President Johnson, and not Seward or Grant, was in line to replace Lincoln if he died. If Johnson had died, an acting President would be appointed until a special election could be held to elect a new President (and not a Vice President).

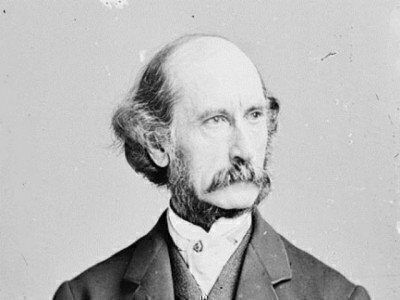

The acting President would have been the president pro tempore of the Senate, Lafayette Sabine Foster of Connecticut.

The Presidential Succession Act of 1792 controlled how the President was replaced if he died in office, quit, or was unable to perform his duties.

The act was changed in 1886 and 1947 to deal with different scenarios. The 20th Amendment addressed what happens if a president-elect can’t take office, and the 25th Amendment cleared up the succession of a new Vice President and what happens when a president is temporarily unable to perform his or her duties.

Back in 1865, Booth had convinced George Atzerodt, an acquaintance, to kill Johnson by setting a trap at the Kirkwood House hotel where the vice president lived. However, Atzerodt lost his nerve and didn’t attempt to kill the Vice President, even though he had a rented room above Johnson’s and a loaded gun was found in the room.

If Atzerodt or another assailant had succeeded, Senator Foster would have been acting President until March 4, 1866. And if Foster weren’t available, Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax would have been next, and last, in line to succeed Lincoln and Johnson.

A special election would have taken place in November 1865, with the Electoral College convening in December 1865, and the presidential inauguration being held on March 4, 1866.

The person charged with the official notification of the states to start the special election process was the secretary of state. Luckily, William Seward survived an attack by assassin Lewis Powell.

If Seward had died, that power may have devolved on the assistant secretary of state, who could perform the duties as an acting secretary of state until a new President named a replacement who was confirmed by the Senate.

The assistant secretary of state on April 15, 1865, was Frederick W. Seward, the son of William Seward. Frederick Seward was also seriously injured defending his father during Powell’s assassination attempt. (He would recover after Powell pistol-whipped him.)

From what we know about Lafayette Sabine Foster, he was a conservative Republican who was named as the president pro tempore of the Senate about a month before Lincoln’s death. Foster only remained in the Senate for another two years, failing in a re-election attempt. He was later a judge in his home state until his death in 1880.

According to his obituary, Foster was “a prominent figure in congressional life, as a clear and forcible debater upon great public questions, and as an unsurpassed presiding officer in the Senate, that he was most widely known and will be best remembered.”

Foster also was cited for being above the politics that led to his Senate defeat in 1866.

“He was no seeker after popularity, certainly he never descended to any truckling arts to secure it, and probably to some extent he lost favor by the high tone of both his character and bearing, and by the selectness of his friendships,” the obituary said.

A New York Times article from 1875 sheds some more light on Foster’s loss of his Senate seat. The Republicans picked another nominee at a caucus in 1866, and Foster signaled his agreement to run as a rival candidate supported by Connecticut’s Democrats. Foster dropped out at the last moment to accept a judge's position in the state.

The Times article said Foster remained bitter about losing his Senate seat.

“He does not appear to be have ever recovered from the disappointment of his defeat in 1866,” the article stated.

And what would have happened in the special presidential election of November 1865? The Republican Party was already split between its Radical and Moderate wings.

General Grant may have run for president as a compromise candidate, but other prominent Republicans included Seward, Colfax, Thaddeus Stevens, and Benjamin Wade.

The Democrats were also divided and had been badly beaten in the 1864 presidential campaign. Former New York Governor Horatio Seymour, the eventual 1868 nominee, was a key player in the party, as was George H. Pendleton, the 1864 vice presidential nominee. General Winfield Scott Hancock had presidential ambitions in later years, and he had personally supervised the executions in the Lincoln assassination case.

The former Confederate states wouldn’t have been involved since they weren’t readmitted to the union.

Benjamin Wade replaced Foster as Senate president pro tempore in 1867 and nearly became acting President in 1868 when President Johnson avoided removal from office by one vote in a Senate trial.

Scott Bomboy is the editor-in-chief of the National Constitution Center