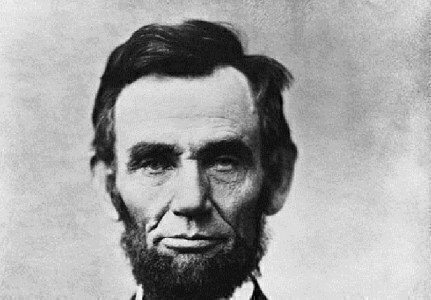

On November 6, 1860, voters in the United States went to the polls in an election that ended with Abraham Lincoln as President, in an act that led to the Civil War. But Lincoln’s victory didn’t happen on that day, and his victory wasn’t assured for months.

Lincoln was the candidate of the newly created Republican Party, which officially wanted to limit the expansion of slavery. The rival Democrats had split into two factions, with Stephen Douglas and John Breckinridge running against Lincoln, and another new party, the Constitutional Union Party, also fielding a candidate.

Lincoln was home in Springfield, Illinois, awaiting news of the national vote. He needed a majority of votes in the Electoral College to win the election. It was assumed he would have the most popular votes, because of the GOP’s strength in the North and West, but he was also guaranteed of not having a majority of the popular vote.

Based on warnings from southern states, it was expected that at least seven states would take steps to leave the Union if and when Lincoln was elected, and well before he was inaugurated as President in March 1861.

On the New York Times’ Disunion blog, Jamie Malanowski provided a detailed depiction of the scene in Springfield as news of the national votes rolled in.

Lincoln and his team huddled in a telegraph office waiting for the key results from New York and Pennsylvania.

“The advisers paced the floorboards, jumping at every eruption of the rapid clacking of Morse’s machine, while the nominee parked on the couch, seemingly at ease with either outcome awaiting him,” said Malanowski.

Shortly before 2 a.m., Lincoln’s election was confirmed in a telegram from New York. As the wild public celebrations started, Lincoln calmly walked home, told his wife he’d won the election, and he turned in for the evening.

As the votes were counted, Lincoln had about 40 percent of the popular vote and 180 electoral votes, compared with 133 for his opponents combined.

But the southern secession threats cast a pall over the upcoming Electoral College voting process: What if the southern states refused to take part in the Electoral College? Or what if a unified front to avoid secession could convince enough “faithless electors” to switch sides to derail the election?

Lincoln expert Howard Holzer detailed that problem in an essay for the Gilder Lehrman Institute.

“Lincoln and his inner circle worried that Democratic electors might yet unify around a single candidate—or worse, that Republicans, worried about secession, might themselves look for alternatives to Lincoln,” Holzer said. “In fact, several New York Republicans did suggest dumping Lincoln in order to save the Union.”

And what if the southern states boycotted the Electoral College?

“If these states did not participate in the traditional process, could the Electoral College proceed? What would constitute a quorum? No one, least of all Lincoln, knew the answers to these vexing questions,” said Holzer.

In the end, the southern states did take part in the Electoral College process, and Lincoln’s election was certified in Congress in February 1861. But there was a greater than normal military presence on Capitol Hill.

By the time Lincoln became President in March 1861, replacing the ineffective James Buchanan, seven southern states had left the Union – all before Lincoln’s election was certified on February 15, 1861 in Congress.