In December 1944, the Supreme Court handed down one of its most controversial decisions, which upheld the constitutionality of internment camps during World War II. Today, the Korematsu v. United States decision has been rebuked but was only finally overturned in 2018.

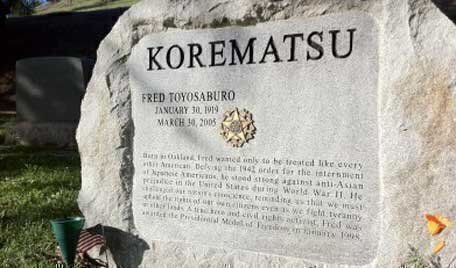

The Court ruled in a 6 to 3 decision that the federal government had the power to arrest and intern Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu under Presidential Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He issued the order after fears generated by the Japanese Pearl Harbor attack made the safety of America’s West Coast a priority. Roosevelt directed the military to isolate any citizen, if needed, from a 60-mile-wide coastal area from Washington state to California and extending inland into southern Arizona.

The Court ruled in a 6 to 3 decision that the federal government had the power to arrest and intern Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu under Presidential Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He issued the order after fears generated by the Japanese Pearl Harbor attack made the safety of America’s West Coast a priority. Roosevelt directed the military to isolate any citizen, if needed, from a 60-mile-wide coastal area from Washington state to California and extending inland into southern Arizona.

Korematsu was arrested for going into hiding in Northern California after refusing to go to an internment camp. Korematsu appealed his conviction through the legal system, and the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case in October 1944. The court had heard a similar case in 1943, Hirabayashi v. United States, and decided that Gordon Hirabayashi, a college student, was guilty of violating a curfew order.

The Korematsu v. United States decision on December 18, 1944, referenced the Hirabayashi case, but it also ruled on the ability of the military, in times of war, to exclude and intern minority groups. Justice Hugo Black, writing for the majority, included a paragraph that is still debated today and that established the judicial review doctrine of “strict scrutiny” applied to laws which target certain suspect groups: “It should be noted, to begin with, that all legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are immediately suspect. That is not to say that all such restrictions are unconstitutional. It is to say that courts must subject them to the most rigid scrutiny. Pressing public necessity may sometimes justify the existence of such restrictions; racial antagonism never can,” Black said.

Later in the decision, Black argued the necessity of the military’s decision.

“Korematsu was not excluded from the Military Area because of hostility to him or his race. He was excluded because we are at war with the Japanese Empire, because the properly constituted military authorities feared an invasion of our West Coast and felt constrained to take proper security measures, because they decided that the military urgency of the situation demanded that all citizens of Japanese ancestry be segregated from the West Coast temporarily,” he said.

In subsequent years, the American internment policy has been met with harsh criticism.

One 1948 law provided reimbursement for property losses incurred by interned Japanese-Americans. In 1988, Congress awarded restitution payments of $20,000 to each survivor of the 10 camps. As part of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, Congress apologized "on behalf of the people of the United States for the evacuation, relocation, and internment of such citizens and permanent resident aliens." President Bill Clinton awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Korematsu in 1998, and President Barack Obama bestowed the same honor on Hirabayashi in 2012.

Federal courts also overturned the original convictions of Hirabayashi and Korematsu. And in June 2018, two Supreme Court justices criticized the decision and agreed that it no longer has the force of precedent as part of a ruling on the Trump administration’s “travel ban” proclamation in Trump v. Hawaii. In Trump v. Hawaii, the Court ruled 5-4 to uphold the president’s proclamation, with Chief Justice Roberts writing the majority opinion and Justice Sotomayor writing a dissent.

In his opinion, Chief Justice Roberts strongly objected to analogies of the Trump v. Hawaii case to Black’s majority 6-3 decision in Korematsu. “Whatever rhetorical advantage the dissent may see in doing so, Korematsu has nothing to do with this case,” Roberts said.

But he then offered the most powerful rebuke of Korematsu at the Supreme Court since Robert Jackson, Owen Roberts, and Frank Murphy dissented in the original case:

“The forcible relocation of U. S. citizens to concentration camps, solely and explicitly on the basis of race, is objectively unlawful and outside the scope of Presidential authority. But it is wholly inapt to liken that morally repugnant order to a facially neutral policy denying certain foreign nationals the privilege of admission,” Roberts said.

“The dissent’s reference to Korematsu, however, affords this Court the opportunity to make express what is already obvious: Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and to be clear ‘has no place in law under the Constitution,’” Roberts said, quoting Justice Jackson’s 1944 dissent.

In her dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor (joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg), despite disagreeing with the majority on the merits, considered Roberts’ comments in the majority decision as proof the Court had finally overturned Korematsu. “Today, the Court takes the important step of finally overruling Korematsu, denouncing it as ‘gravely wrong the day it was decided.’ This formal repudiation of a shameful precedent is laudable and long overdue,” Sotomayor said.