On May 11, 1894, several thousand train workers started an unannounced strike at the Pullman Company in Illinois. Over the next few months, dozens of workers would die in strike-related violence, and the President and Supreme Court would finally become involved in the strike’s outcome.

The Pullman Company built and leased passenger train cars, thousands of which were in operation around the United States by 1893. George Pullman also built a planned community or company town for his workers in Illinois, where workers enjoyed many amenities but were also financially dependent on the Pullman Company for their homes and utilities.

After a severe depression in 1893, wages fell about 25 percent for the Pullman workers while living costs remained the same. The workers then sought out union representation. Former railroad worker Eugene V. Debs and his American Railway Union, which had won a strike earlier in 1894, became involved in the Pullman situation. The May 11 “wildcat” strike wasn’t directly organized by the ARU, but Debs and the union quickly became involved in the strike as it escalated.

In June 1894, the ARU called for a national boycott of Pullman cars by its union members, who managed the flow of railway traffic west of Chicago. The Pullman Company attempted to call Debs’ bluff, and by late June, at least 125,000 ARU members had walked off the job in support of the Pullman workers.

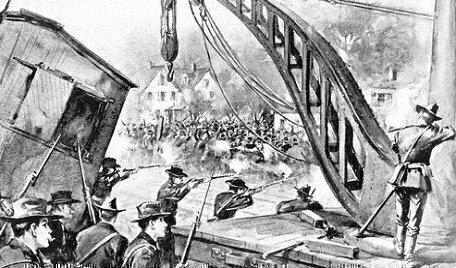

Violence related to the strikes became an issue, as did U.S. mail delivery system’s inability to operate in strike-affected regions. When Illinois governor John P. Altgeld refused to ask for federal troops to intercede in the strike, U.S. Attorney General Richard Olney, who had a close relationship with the railway industry, asked for the first-ever federal injunction to block a strike. However, the strikers mostly ignored the injunction, a court order which said they had to stop striking and return to work. President Grover Cleveland then sent about 2,000 troops to Illinois to enforce the injunction, and more violence ensued.

Debs and other union leaders were arrested after the injunction was ignored. Debs eventually spent six months in jail on related charges and the ARU was broken up. Debs hired a former railroad attorney, Clarence Darrow, to represent him at trial.

Debs, Darrow and former Senate Lyman Trumbull challenged the injunction’s legality and Debs’s confinement, eventually appealing all the way to the Supreme Court. In 1895, a unanimous Court decided the case of In re Debs, holding that the federal government could issue a strike injunction as part of its role in regulating interstate commerce and in order to protect the general welfare of the people.

“In the exercise of those powers, the United States may remove everything put upon highways, natural or artificial, to obstruct the passage of interstate commerce, or the carrying of the mails,” said Justice David Brewer.

However, Brewer acknowledged the importance of the issue nationally and the effectiveness of Darrow’s arguments.

“A most earnest and eloquent appeal was made to us in eulogy of the heroic spirit of those who threw up their employment, and gave up their means of earning a livelihood, not in defense of their own rights, but in sympathy or and to assist others whom they believed to be wronged,” Brewer wrote.

But he added that the court and electoral systems were the best venues to settle such disputes.

“We yield to none in our admiration of any act of heroism or self-sacrifice, but we may be permitted to add that it is a lesson which cannot be learned too soon or too thoroughly that, under this government of and by the people, the means of redress of all wrongs are through the courts and at the ballot box, and that no wrong, real or fancied, carries with it legal warrant to invite as a means of redress the cooperation of a mob, with its accompanying acts of violence.”

After the Pullman strike and the Supreme Court decision, Debs and Darrow would remain prominent figures in the labor and legal fields into the twentieth century.