August 2, 1776, is one of the most important but least celebrated days in American history when 56 members of the Second Continental Congress started signing the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia.

Officially, the Congress declared its freedom from Great Britain on July 2, 1776, when it approved a resolution in a unanimous vote.

Officially, the Congress declared its freedom from Great Britain on July 2, 1776, when it approved a resolution in a unanimous vote.

After voting on independence on July 2, the group needed to draft a document explaining the move to the public. It had been proposed in draft form by the Committee of Five (John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson) and it took two days for the Congress to agree on the edits. Thomas Jefferson was the main author.

Once the Congress approved the actual Declaration of Independence document on July 4, it was sent to a printer named John Dunlap. About 200 copies of the Dunlap Broadside were printed, with John Hancock’s name printed at the bottom. Today, 26 copies remain. Then on July 8, 1776, Colonel John Nixon of Philadelphia read a printed Declaration of Independence to the public for the first time on what is now called Independence Square.

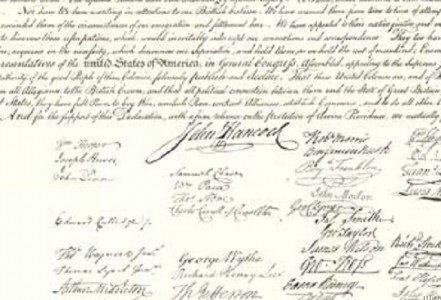

Many members of the Continental Congress started to sign an engrossed version of the Declaration on August 2, 1776, in Philadelphia. John Hancock’s famous signature was in the middle, because of his status as President of the Congress. The other delegates signed by state delegation, starting in the upper right column, and then proceeding in five columns, arranged from the northernmost state (New Hampshire) to the southernmost (Georgia).

Historian Herbert Friedenwald explained in his 1904 study of the Second Continental Congress that the signers on August 2 weren’t necessarily the same delegates at the Congress in early July when the Declaration was proposed and approved.

“Attempting now to determine the names of some of those who were present on the day officially appointed for signing the engrossed document (August 2), we reach the conclusion that a far greater number than has generally been supposed were not in Philadelphia on that day either,” said Friedenwald, who determined discrepancies between the delegates perceived to sign the document on July 4 and the actual delegates who started signing the Declaration on August 2.

Friedenwald said there were 49 delegates in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776, but only 45 would have been able to sign the document on that day. Seven delegates were absent. New York’s eight-person delegation didn’t vote at the time, while it awaited instructions from home, so it could never have signed a document on July 4, he said.

Richard Henry Lee, George Wythe, Elbridge Gerry, Oliver Wolcott, Lewis Morris, Thomas McKean, and Matthew Thornton signed the document after August 2, 1776, as well as seven new members of Congress added after July 4. Seven other members of the July 4 meeting never signed the document, Friedenwald said.

However, the signers’ names weren’t released publicly until early 1777, when Congress allowed the printing of an official copy with the names attached. On January 18, 1777 printer Mary Katherine Goddard’s version printed in Baltimore indicated the delegates “desired to have the same put on record,” and there was a signature from John Hancock authenticating the printing.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.