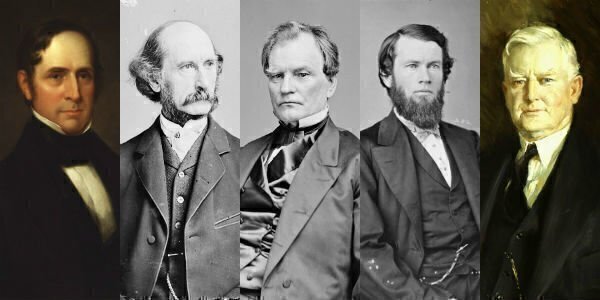

What do Benjamin Wade, Willie P. Mangum, Lafayette S. Foster, Thomas W. Ferry, and John Nance Garner all have in common? If not for a last-second decision, or a twist of fate, they might have become Acting President of the United States, in an era before the 25th Amendment was ratified.

This week is the anniversary of Vice President Gerald Ford’s ascension to the presidency in 1974 after Richard Nixon’s resignation. But without the 25th Amendment, it would have been Carl Albert, and not Ford, in the White House.

To paraphrase a term President Ford used when he pardoned Nixon, the 25th Amendment’s ratification in 1967 ended “our long national nightmare” about the rules of presidential succession.

The 25th Amendment allows a President to appoint a Vice President in the case of a vacancy, with the approval of Congress. The idea gained momentum after President John F. Kennedy’s death in 1963, when Lyndon Johnson served out the remainder of Kennedy’s term without his own Vice President.

The 25th Amendment also clears up any questions about the Vice President’s ability to succeed a President who dies in office, resigns, or is removed from office. It also provides guidelines for how the President, Vice President, Congress and the cabinet can deal with situations when a President is temporarily or permanently unable to discharge his or her duties.

Until 1967, the succession rules were based on a loosely defined Article II, Section 1, of the Constitution; a precedent set by President (or Acting President, as his opponents believed) John Tyler in 1841; and presidential succession acts passed by Congress that named the next-in-line to the White House after the President and Vice President.

The office of Vice President has been vacant 18 times because of the deaths of eight Presidents and seven Vice Presidents in office, two vice presidential resignations, and one presidential resignation. So in several hypothetical cases, someone other than the Vice President might have assumed the duties of the President if an assassination attempt, an accident, or a constitutional problem led to a presidential vacancy. A few examples are below:

Willie P. Mangum. If Mangum’s name doesn’t seem familiar, that’s because he was the Senate president pro tempore in 1844. Between 1792 and 1886, the president pro tempore was second-in-line to the White House, after the Vice President.

After the passing of President William Henry Harrison in 1841, Tyler assumed the presidency by boldly declaring he was entitled to the full power and title of President. Although Tyler had been Harrison’s Vice President, the issue of succession wasn’t clearly spelled out in the Constitution—whether the Vice President would simply act as President for a period in case of the President’s death or resignation, or whether the Vice President then became the actual President.

But Tyler himself was nearly killed in a shipboard explosion in 1844. President Tyler was stopped by a dignitary on his way up to a deck to witness a naval gun display on the USS Princeton. The gun exploded, killing the Secretary of State and the Secretary of the Navy instead. Had Tyler died, Magnum would have become President since the office of Vice President was vacant.

Lafayette S. Foster. Foster was the Senate president pro tempore in 1865 when Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. Part of the plot to kill Lincoln included an assassination attempt on Vice President Andrew Johnson.

John Wilkes Booth had convinced George Atzerodt to kill Johnson at a hotel where the Vice President was staying. Atzerodt camped out in a room above Johnson’s room, but he decided on that fateful night to abandon the attempt, and he went out drinking instead.

Atzerodt was executed in July 1865 for his role in the conspiracy. Had he killed the unsuspecting Johnson, Foster would have been Acting President, until an election could be held to choose a new President in December 1865.

Benjamin Wade. It was Wade who had replaced Foster as Senate president pro tempore by 1868 when President Andrew Johnson was impeached by the House and put on trial in the Senate.

One of the theories about how Johnson escaped a guilty verdict by one vote in the Senate was that there was a contingent of Senators who didn’t want Wade, a Radical Republican, as Acting President since the office of Vice President was vacant.

Said one newspaper at the time, “Andrew Johnson is innocent because Ben Wade is guilty of being his successor.”

Thomas W. Ferry. Ferry’s brush with the presidency was more of a theoretical one, but all too real under the election laws of 1876.

In that contentious presidential election, the Democratic candidate, Samuel Tilden, won the popular vote against Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, but the electoral vote was in dispute.

Different sets of electors were submitted by three states that would decide the election. Since there wasn’t a constitutional fix for the problem, Congress appointed a 15-person commission, including five Supreme Court Justices, to settle the disputed race. The commission ruled in favor of Hayes just two days before the inauguration. The votes were approved in Congress at 4:10 a.m. on March 2.

Ferry was the Senate president pro tempore at the time and would have been the Acting President if the Electoral College vote wasn’t certified on March 4, 1877. In fact, Ferry may have believed he was President for one day, since he was unaware that Hayes took the presidential oath in private on March 4, a Sunday.

John Nance Garner. Garner almost became President under the terms of a constitutional amendment ratified just weeks before an assassination attempt on President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933.

The 20th Amendment was ratified on January 23, 1933, and it made provisions for the Vice President-elect—in this case, Garner—to assume the presidency if the President-elect died before taking the oath of office.

On February 15, 1933, just 23 days after the amendment went into force, assassin Giuseppe Zangara opened fire on a car in Miami that contained President-elect Roosevelt. He missed Roosevelt but fatally wounded Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak.

Garner was a conservative Southern Democrat who wound up opposing Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. He also would have sought to replace Roosevelt as President in 1940 if FDR hadn’t decided to run for a third term. Garner was ultimately replaced on the ticket by Henry Wallace.