Updated: On Jan. 17, 2025, President Joseph Biden said in a statement that he believes the "Equal Rights Amendment has cleared all necessary hurdles to be formally added to the Constitution as the 28th Amendment." According to a report from NPR, the White House said Biden wil not order the Archivist of the United States to certify the proposed amendment.

Original Story: In recent weeks, several groups have asked outgoing President Joe Biden to order the Archivist of the United States to certify the Equal Rights Amendment (or ERA) as the next amendment to the Constitution. Although the ERA’s ratification deadline passed in 1982, some people supporting the ERA believe that deadline is not in effect and the ERA should be the law of the land.

On Dec. 17, 2024, the Archivist’s office responded to the latest request from ERA supporters: “At this time, the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) cannot be certified as part of the Constitution due to established legal, judicial, and procedural decisions,” said Archivist of the United States Dr. Colleen Shogan and Deputy Archivist William J. Bosanko. The Archivist cited opinions from the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Council issued in 2020 and 2022 that stated that the “the ratification deadline established by Congress for the ERA is valid and enforceable,” the ERA had expired and was therefore no longer pending before the states.

On Dec. 17, 2024, the Archivist’s office responded to the latest request from ERA supporters: “At this time, the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) cannot be certified as part of the Constitution due to established legal, judicial, and procedural decisions,” said Archivist of the United States Dr. Colleen Shogan and Deputy Archivist William J. Bosanko. The Archivist cited opinions from the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Council issued in 2020 and 2022 that stated that the “the ratification deadline established by Congress for the ERA is valid and enforceable,” the ERA had expired and was therefore no longer pending before the states.

The proposed amendment’s Section 1 reads as follows: “Equality of Rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any state on account of sex.” Sections 2 and 3 establish that Congress has the power to enforce laws related to the amendment, which goes into effect two years after ratification.

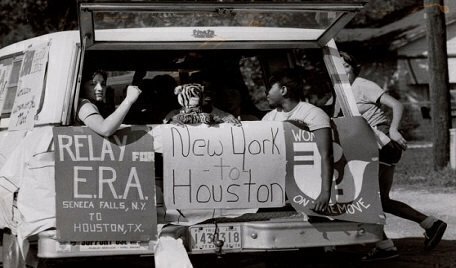

Under the Constitution’s Article V, two-thirds of Congress approved the proposed amendment’s language in 1972 and sent the ERA to the states for ratification where 38 states were needed to add the amendment to the Constitution. The proposing clause included in a joint resolution sent to the states with a paragraph that placed a seven-year deadline on the ratification process, of March 22, 1979. In that period, 35 states ratified the amendment, and Congress then extended the deadline by three years to 1982. However, no other states approved the ERA by the new deadline.

In recent years, Nevada (2017), Illinois (2018), and Virginia (2020) voted to approve the ERA, setting the stage for the current debate. Those states, some groups and scholars have argued that the ERA should be considered as a ratified amendment, since a total of 38 states approved the ERA, including the three states which voted after the deadline established by Congress. Their arguments include the theory that Congress did not properly include the deadline in the amendment language sent to the states, or Congress lacks the power to establish a permanent ratification deadline.

The Dispute Over a Paragraph

One area of dispute is the plain language of the Constitution’s Article V, which establishes the basic process of amending the Constitution.

Among the groups and people that believe the ERA can and should be the 28th Amendment to the Constitution is the League of Women Voters, the American Bar Association (ABA), and Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand of New York. In a recent editorial, Gillibrand wrote that the ratification deadline established was “meaningless” and the 2020 Office of Legal Council memo on the ERA was wrong. “The [2020] memo contended that the E.R.A. is no longer valid because it failed to meet the seven-year deadline that Congress initially set and then, when the ratification effort fell three states short, extended until 1982,” wrote Gillibrand in a Dec. 15 oped in The New York Times. “But the deadline was meaningless. The Constitution says nothing about a deadline for amending it.”

In August 2024, the ABA passed a resolution that “a deadline for ratification of an amendment to the U.S. Constitution is not consistent with Article V of the Constitution” and that states lacked the ability to rescind amendment ratifications.

The Supreme Court considered a similar question in Dillon v. Gloss (1921), when a challenge was made to the 18th Amendment, which established Prohibition. The challenger claimed the inclusion of a seven-year ratification deadline by Congress in the amendment was unconstitutional. In his unanimous opinion, Justice Willis Van Devanter wrote that “We do not find anything in [Article V] which suggests that an amendment, once proposed, is to be open to ratification for all time, or that ratification in some of the states may be separated from that in others by many years and yet be effective. We do find that which strongly suggests the contrary.”

“The period of seven years, fixed by Congress in the resolution proposing the Eighteenth Amendment was reasonable,” the Court concluded.

A similar challenge was presented to the Court in Coleman v. Miller (1939) in a dispute over a proposed Child Labor Amendment to the Constitution. In a 7-2 decision, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes cited the Dillon precedent. “Our decision that the Congress has the power under Article V to fix a reasonable limit of time for ratification in proposing an amendment proceeds upon the assumption that the question—what is a reasonable time—lies within the congressional province.” Justices Felix Frankfurter, William O. Douglas, Owen J. Roberts, and Hugo Black agreed with Chief Justice Hughes on the ratification deadline question.

In his dissent, Justice Pierce Butler, joined by Justice James C. McReynolds, also agreed with the majority on the deadline question. “We definitely held [in Dillion] that Article V impliedly requires amendments submitted to be ratified within a reasonable time after proposal, that Congress may fix a reasonable time for ratification, and that the period of seven years fixed by the Congress was reasonable.”

According to the Congressional Research Service, when Nevada and Illinois ratified the ERA in 2017 and 2018, the two states referred to a different section of the Coleman opinion as supporting the argument that the Equal Rights Amendment could still be ratified after the 1982 deadline had passed since the deadline was included in the resolving clause of the joint resolution of Congress, and not in the actual text of the amendment. The states believed that Congress has the power “to determine the validity of the state ratifications” after a ratification deadline has passed.

In a newer court case, Nevada, Illinois, and Virginia filed suit in federal court after the Archivist refused in January 2020 to certify the Equal Rights Amendment as the Constitution’s 28th Amendment. In Virginia v. Ferriero, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia dismissed the lawsuit due to a lack of standing. The District of Columbia Court of Appeals then considered the case as Illinois v. Ferriero after Virginia declined to continue in the dispute. The appeals court ruled that the states had failed to establish that the Archivist was compelled to certify the ERA and that the states could not cite a persuasive authority that the ratification deadline’s inclusion in the resolving clause rendered the deadline as invalid.

After the Archivist’s public statement last month that she would not publish the ERA, the Associated Press reported that the Biden administration believed Congress should act to eliminate the ratification deadline. And the OLC’s January 2022 opinion on the question found that nothing in the OLC’s previous opinions prevented Congress from acting on the ERA. “The 2020 OLC Opinion is not an obstacle either to Congress’s ability to act with respect to ratification of the ERA or to judicial consideration of the pertinent questions,” concluded Assistant Attorney General Christopher Schroeder.

However, another open question exists. Between 1973 and 1978, Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Tennessee passed laws to rescind their prior ratifications of the ERA. In 1982, a federal court in Idaho ruled that states could rescind their ratifications of an amendment before three-fourths of the states approved an amendment’s addition to the Constitution. The Supreme Court vacated the Idaho case as moot since the ERA’s deadline had passed, leaving that question unresolved.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.